Suppose there was a star 1,480 light years away which was orbited by a vast cluster of alien artefacts - artefacts something like Iain M. Banks' Culture Orbitals.

And suppose the Kepler space telescope, currently surveying 145,000 stars for exoplanets, happened to observe it. What exactly would it see?

We actually know the answer to this question: something very like KIC 8462852.

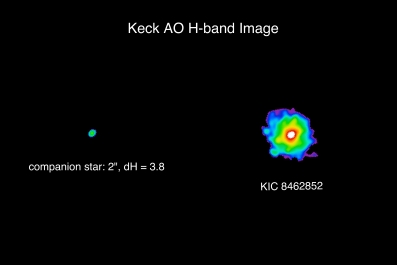

"KIC 8462852 has been causing ripples since 2011 because while we do seem to be seeing something passing between its light and us, that something is not a planet but a large number of objects in motion around the star. Some of the dips in starlight are extremely deep (up to 22 percent), and they are not periodic.See the Centauri Dreams post for full details. It's worth noting that if we ever get around to building large structures in orbit around our own sun, alien observers thousands of light years away will be able to see them.

Here’s how Phil Plait describes the situation:

…it turns out there are lots of these dips in the star’s light. Hundreds. And they don’t seem to be periodic at all. They have odd shapes to them, too. A planet blocking a star’s light will have a generally symmetric dip; the light fades a little, remains steady at that level, then goes back up later. The dip at 800 days in the KIC 8462852 data doesn’t do that; it drops slowly, then rises more rapidly. Another one at 1,500 days has a series of blips up and down inside the main dips. There’s also an apparent change in brightness that seems to go up and down roughly every 20 days for weeks, then disappears completely. It’s likely just random transits, but still. It’s bizarre.

A ragged young debris disk would be the natural conclusion, but arguing against this is the fact that we don’t see the infrared excess that a dusty disk would create." ...

Is the companion star transiting and disrupting a comet cloud?

We’ve often discussed cometary disruptions in these pages, speculating on what the passage of a nearby star might do to comets in the Oort Cloud. As per the images above, it’s a natural speculation that the anomalies of KIC 8462852 are the result of a similar scenario.

...

The paper, as we saw yesterday, explores other hypotheses but settles on comet activity as the likeliest, given the data we currently have. The kind of huge collision between planets that would produce this signature would also be rich in infrared because of the sheer amount of dust involved, and we don’t see that. You can see why all this would catch the eye of Jason Wright (Penn State), who studies SETI of the Dysonian kind, involving large structures observed from Earth. Because if we’re looking at cometary chunks, some of these are extraordinarily large.

Update: Centauri Dreams has yet another post on this object today.

---

October 27th 2015: Here's an updated view from Oxford University.

Bruce Schneier points to the following article:

"The three men who showed up at Michael Usry’s door last December were unfailingly polite. They told him they were cops investigating a hit-and-run that had occurred a few blocks away, near New Orleans City Park, and they invited Usry to accompany them to a police station so he could answer some questions. Certain that he hadn’t committed any crime, the 36-year-old filmmaker agreed to make the trip.You can see why the police might have wanted to do this: the article goes on to state, disparagingly,

The situation got weird in the car. As they drove, the cops prodded Usry for details of a 1998 trip he’d taken to Rexburg, Idaho, where two of his sisters later attended college—a detail they’d gleaned by studying his Facebook page. “They were like, ‘We know high school kids do some crazy things—were you drinking? Did you meet anybody?’” Usry recalls. The grilling continued downtown until one of the three men—an FBI agent—told Usry he wanted to swab the inside of Usry’s cheek but wouldn’t explain his reason for doing so, though he emphasized that their warrant meant Usry could not refuse.

The bewildered Usry soon learned that he was a suspect in the 1996 murder of an Idaho Falls teenager named Angie Dodge. Though a man had been convicted of that crime after giving an iffy confession, his DNA didn’t match what was found at the crime scene. Detectives had focused on Usry after running a familial DNA search, a technique that allows investigators to identify suspects who don’t have DNA in a law enforcement database but whose close relatives have had their genetic profiles cataloged. In Usry’s case the crime scene DNA bore numerous similarities to that of Usry’s father, who years earlier had donated a DNA sample to a genealogy project through his Mormon church in Mississippi. That project’s database was later purchased by Ancestry, which made it publicly searchable—a decision that didn’t take into account the possibility that cops might someday use it to hunt for genetic leads.

Usry, whose story was first reported in The New Orleans Advocate, was finally cleared after a nerve-racking 33-day wait—the DNA extracted from his cheek cells didn’t match that of Dodge’s killer, whom detectives still seek. But the fact that he fell under suspicion in the first place is the latest sign that it’s time to set ground rules for familial DNA searching, before misuse of the imperfect technology starts ruining lives."

" In the United Kingdom, a 2014 study found that just 17 percent of familial DNA searches “resulted in the identification of a relative of the true offender.”but in the absence of other evidence, 17% is a lot better than zero for most detectives.

I suspect it would be easy to do much the same with 23andMe, even without invoking warrants and secret agreements with law enforcement. As with most things genetic, this issue is only going to get bigger.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Keep it polite and no gratuitous links to your business website - we're not a billboard here.